Adventure playgrounds offer kids space to build resilience, self-confidence and courage.

- By

- Parker Barry

We have witnessed a seismic shift over the past few generations — a gradual but dramatic decline in children’s free-play opportunities and an increase in childhood mental and emotional disorders. Play is the crucial childhood goal — it’s how kids develop a sense of self, learn how to make their own decisions, solve problems, regulate emotions, exert control, follow rules, make friends and experience joy (Gray, 2011). Parents who create supportive environments for open-ended, self-directed, creative play also provide opportunities for their kids to gain a sense of mastery and competence in their experiences. That self-efficacy sets the stage for a lifetime of higher self-esteem (Harter, 1988, Coopersmith, 1967) and other health benefits. No pressure.

Developmental psychologist Peter Gray notes the importance of fostering resilience through free-play: “Children are designed by nature to teach themselves emotional resilience by playing in risky, emotion-inducing ways. We deprive children of free, risky play, ostensibly to protect them from danger. In the long run, we endanger them far more by preventing such play than by allowing it. And, we deprive them of fun.”

Adventure playgrounds

In 1931, a Danish landscape architect, Carl Theodor Sørensen, noticed that kids were playing everywhere other than the playgrounds he had designed for them, including construction sites. He proposed the idea to build deliberate “junk playgrounds,” particularly for city kids who have less access to natural outdoor play. His vision came to fruition with the first site in 1943 at Emdrup, Denmark. This playground grew out of the need for a safe place where kids could play freely without inciting the German occupying forces. These dedicated “junkyards,” as they were originally called, were stocked with “loose parts” of discarded wood, containers, fabric, and even old train engines, lifeboats and discarded buses. These elements provided a variety of stimulation to be manipulated, destroyed and rebuilt into new inventions. These junk playgrounds began to spread through Denmark, Europe and North America, taking expansive root in the UK.

Lady Marjory Allen of Hurtwood, a British landscape architect and children’s advocate, had been dismayed by “asphalt square” playgrounds with adult-manufactured rigid mechanical equipment that didn’t allow kids to act on their environment or fully express creative ideas. Many adults at the time also noticed that kids enjoyed playing in the rubble of bombed out buildings after World War II. After seeing the Danish junk playgrounds in 1946, Lady Allen set out to design similar sites with as little adult supervision as possible, and the term “adventure playground” was born.

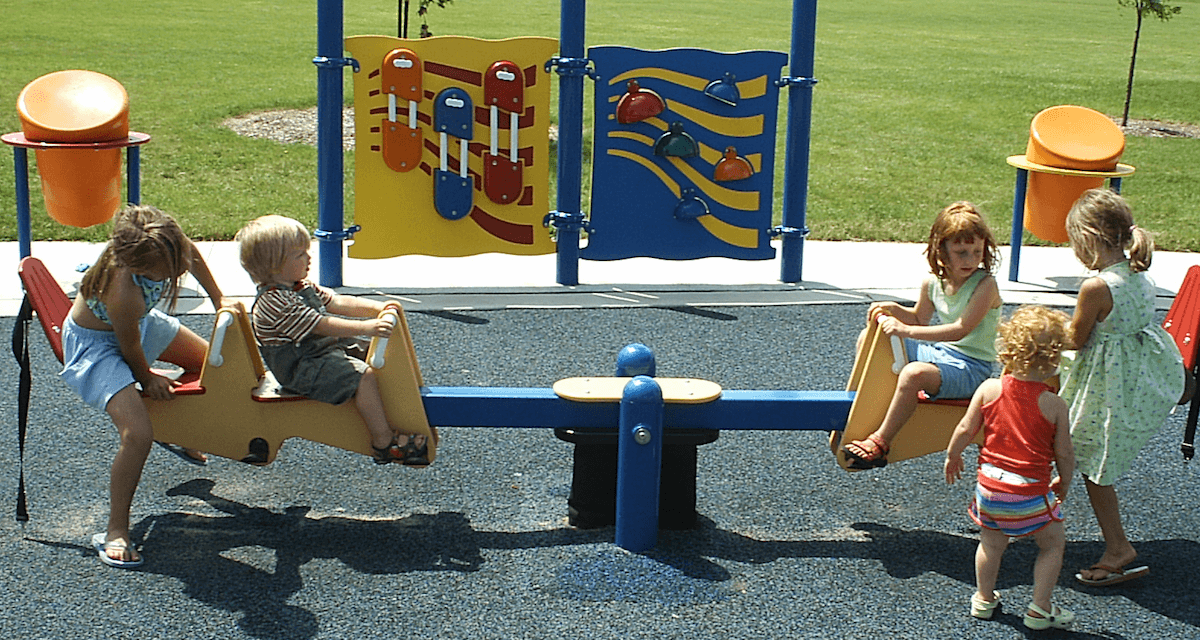

The idea was that kids should confront risks and then conquer them alone, building resilience, self-confidence and courage. Well-trained adult “playworkers” were provided for supervision and would help when asked or needed, particularly in dealing with tools. However, they did not teach, direct, impose or interfere with creative expression. Today, playwork is a respected and well-paid profession in Europe and Japan. In Europe, it is so highly valued that one can get an undergraduate degree in playwork.

The first U.S. adventure playground, called “The Yard,” opened in 1949 in Minneapolis. The next known site was in New York City in the early 1970s and only lasted a few years. By the late ’70s there were 19 around the country, but they began to disappear due to the lack of public funding, contrary to the belief that their demise was due to Americans’ litigious nature and protective parenting (Bergin Wilson, 2017). There are currently five adventure playgrounds around the country. They have recently been making a comeback and are, once again, becoming quite active in New York City.

play:groundNYC

Three years ago, a group of artists, educators, parents and activists were dismayed at the lack of free, self-directed play in New York City. They came together to create a series of one-day pop-up play days in the park, which have since evolved into play:groundNYC, one of the newest adventure playgrounds in the U.S. It is situated on Governors Island, a thriving public park five minutes from Manhattan by ferryboat. The site was designed to provide kids (6+) with space and materials for self-directed play, discovery and productive risk-taking. The large variety of materials and tools provided include nails, hammers and saws, paint, tires, wood and fabrics.

“play:groundNYC is 50,000 square feet of magic,” says executive director Rebecca Faulkner. “This is a place where children can choose their own adventures, build their own structures and dream big!” Faulkner’s dad played in the ruins of bombed out buildings in East London after the Blitz. “It’s in my family’s DNA,” she said.

Their website has a message for parents: “Expect your child to get messy! Our junkyard play area is for kids only.” Adults can watch from a lovely patch of grassy shade across the way, but are asked to let the kids play on their own, as playworkers help their children navigate the difference between a risk and a hazard. Faulkner reminds parents who are leaning on the fence, “Your children are having a great time; the grass is right over there; you can keep an eye on them from there.”

“It’s really hard for parents to let their kids just be,” says Jenea Singleton, the lead weekend playworker, “but if the parents are around, the kids are really cautious and they’ll think more about the reaction they’re going to get instead of what they’re actually doing. Sometimes they actually panic and second-guess themselves.” To her point, children can gain a sense of “learned helplessness” when they believe they lack the ability to handle things on their own — they feel frustrated and give up easily (Dweck, 1978).

Andrew Coats, a dad who brought his two girls four times last summer, was back for more after his daughters begged to return every day the next summer: “They absolutely love it,” Coats said. “As a parent, I am cautious and nervous that they’re going to do something to themselves, but it’s not any different than what I did (as a kid) in a less controlled environment.”

Kristin Gorman, a mom who was visiting for the first time said, “I appreciate that they’re letting the kids roam free and figure things out for themselves. I’m not going to tell you that I don’t have any hesitation right now, because I am a little bit nervous, but I’m letting go, letting him explore and letting him enjoy himself.”

Ellen Sandseter, a professor in early childhood education, observed in her adventure playground study that “Children have a sensory need to taste danger and excitement; this doesn’t mean that what they do has to actually be dangerous, only that they feel they are taking a great risk. That scares them, but then they overcome the fear. Children are highly motivated to play in risky ways, but they are also very good at knowing their own capacities and avoiding risks they are not ready to take, either physically or emotionally. Our children know far better than we do what they are ready for.”

A field trip to the junkyard at play:groundNYC

Playworker Sarah Longwell-Stevens (back, left) observes a boy trying to destroy a boat with scissors. “I walked by and he looked at me like ‘Are you gonna stop me?’” Longwell-Stevens said. “I smiled at him and brought him more tools. Sometimes children need to explore how to be destructive. They don’t have a lot of chances for that. You have to destroy things to learn how they work.”

Playworker Sarah Longwell-Stevens (back, left) observes a boy trying to destroy a boat with scissors. “I walked by and he looked at me like ‘Are you gonna stop me?’” Longwell-Stevens said. “I smiled at him and brought him more tools. Sometimes children need to explore how to be destructive. They don’t have a lot of chances for that. You have to destroy things to learn how they work.”

“The slide was the coolest thing,” Sophie, 8 said, “because it’s kinda like what they have in regular playgrounds, but kids made it.”

“The slide was the coolest thing,” Sophie, 8 said, “because it’s kinda like what they have in regular playgrounds, but kids made it.”

“I was in there the whole day!” said Theda, 7. “My friends who built the tiny shed — it was really fun to play with them. The boys stole almost all the stuff from me and my friends’ hideout and we’re having war now!”

“I was in there the whole day!” said Theda, 7. “My friends who built the tiny shed — it was really fun to play with them. The boys stole almost all the stuff from me and my friends’ hideout and we’re having war now!”

A growing movement

Because Governor’s Island is a destination, play:groundNYC is planning to bring this experience into communities across New York City, mainly through mobile trucks. This way they can be more accessible on a consistent basis and let kids take ownership over their creations. Another major goal, currently in the works, is to make the playground more fully accessible for children with disabilities.

The Alliance for Childhood, a nonprofit organization devoted to restoring play to children’s lives, hopes to eventually see an adventure playground in every community across the U.S. Parks, zoos, children’s museums, after-school programs and camps are increasingly interested in playwork, and Pop-Up Adventure Play offers free resources to help parents, educators and communities create local opportunities. Ideally, parents will create mini-junkyards or free-play opportunities in their living rooms, backyards or broom closets … and then step out of the way and let them play.

Marj Kleinman is a Brooklyn based photographer and children’s media producer with a master’s in educational psychology. All photos by Marj Kleinman.